The British constitution is often said to be ‘unwritten’. This can be misleading term as parts of it are, in fact, written down in various statutes. Rather the constitution is ‘uncodified’; that is there is no one document establishing the basis of the British state (as is the case in the vast majority of other democratic states). The gradual evolution of democracy in the United Kingdom has meant the British constitution exists as a number of individual laws, political conventions and judicial interpretations.

Key features

There are a number of key features of the British constitution:

Constitutional monarchy

The role of the monarchy is largely ceremonial. Although the Queen is the official head of state, the reality is she acts more as a figure head, giving royal assent to legislation following the advice of ministers and promoting the UK during state visits and public engagements. In a political context the monarchy is expected to be impartial and co-operate with the elected government.

Democracy

The British constitution is democratic in that the British electorate govern themselves through parliamentary institutions. This is done by free elections of representatives to parliament.

Parliamentary sovereignty

Another central feature of the British constitution is that of parliamentary sovereignty. This principle means that parliament is the supreme law making body in the UK; it has power to make law or repeal law it has previously passed. There is currently a debate surrounding the true extent of parliamentary sovereignty, including devolution and membership of the European Union. For more information on the role and functions of parliament see the parliament and law making section of the hub.

Parliamentary democracy

The UK adopts a parliamentary democracy, whereby the government (the executive) is drawn directly from parliament (the legislature). This is different from other forms of democracy, such as in the United States, where the executive and legislature are clearly separated.

Cabinet government

Responsibility for the government rests with the cabinet of the Queen’s appointed ministers. This is a committee of politicians who are drawn from and responsible to parliament for the management of the nation’s affairs. Cabinet is collectively responsible for the decisions it makes. For more information on cabinet and its role see the cabinet and ministers section of the hub.

Components of the constitution

There are a number of statutes, conventions and historical events which all form part of the constitution. Some of the legislation includes:

There are a number of statutes, conventions and historical events which all form part of the constitution. Some of the legislation includes:

- 1215: Magna Carta

- 1689: Bill of Rights

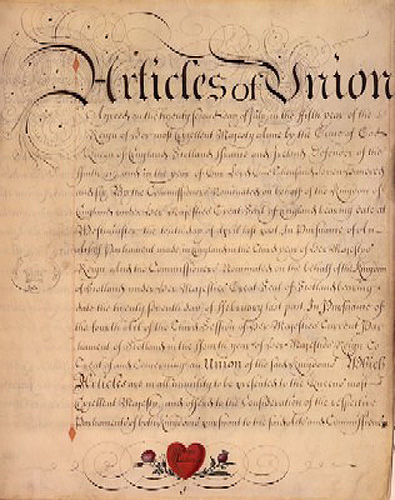

- 1707: Act of Union

- 1832: Reform Act

- 1911 and 1949: Parliament Acts

- 1920: Government of Ireland Act

- 1998: Human Rights Act

- 1998: Scotland Act

- 1998: Government of Wales Act

- 2005: Constitutional Reform Act

Impact of the European Union

In 1973 the UK signed the Treaty of Rome and became a member state of the European Community. This was after parliament passed the European Communities Act 1972, and was subsequently confirmed by a referendum in 1975. Subsequent legislation ratifying other EU treaties has furthered the UK’s level of integration in the EU. The impact of the EU on the UK is a constant topic of debate. The Foreign and Commonwealth Office has recently launched a review assessing the EU’s impact with an aim to make sure the balance of competencies is fair. For more information on the EU and its role see the European Union section of the hub.

Arguably the EU has had an impact on the constitutional principle of parliamentary sovereignty in that much legislation affecting the UK is now decided at a European level, rather than by parliament. The UK is duty bound to apply this legislation under its treaty obligations. Strictly speaking, however, parliament could decide to repeal the European Communities Act and other legislation, so the amount of parliamentary sovereignty actually lost is contested. The recent EU Act aims to clarify this relationship and requires referenda to be held in the event of any transfer of significant power from the UK to Europe.

Reform

Various pressure groups, for example Unlock Democracy, are campaigning for a more transparent, written constitution. However, the government itself has often initiated reforms in response to public opinion or the political context. Current examples of this include the Fixed Term Parliaments Act and the House of Lords Reform bill.

Recommended reading

E-books are only available with a University of Portsmouth login.

Birch, A. H. (1998). The British System of Government (10th ed.). London: Routledge.

Blain, N. (2003). Media, Monarchy and Power. Bristol: Intellect Books.

Bogdanor, V. (2009). The New British Constitution. Oxford: Hart.

English, R. and Townshend, C. (Eds.). (1999). The State: Historical and Political Dimensions. London: Routledge.

Hennessy, P. (1995). The Hidden Wiring: Unearthing the British Constitution. London: Gollancz.

Norton, P. (2010). The British Polity (5th ed.). New Jersey: Pearson.

Other resources

While the British constitution is still uncodified, the Cabinet Office has been attempting to draw various aspects of it together in the form of a Cabinet Manual.

The Constitution Society is an independent organisation promoting understanding of the British constitution and encouraging debate.

A number of papers on constitutional affairs are produced by the House of Commons Library Parliament and Constitution Centre.

The Constitution Unit at University College London has a number of research projects and publications examining current debates surrounding the British constitution, including constitutional reform.

The Guardian newspaper’s website has a section devoted to constitutional reform, which is a good source for the latest news in constitutional affairs.

The House of Lords Constitution Committee scrutinizes proposed legislation that has constitutional implications.

This interesting article on the BBC News website gives highlights the debate around the advantages and disadvantages of an unwritten constitution.